‘It’s not been enough to carry the day’: Why the Victoria’s Secret rebrand is over

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Business of Fashion, an editorial partner of CNN

The radical transformation of Victoria’s Secret is over.

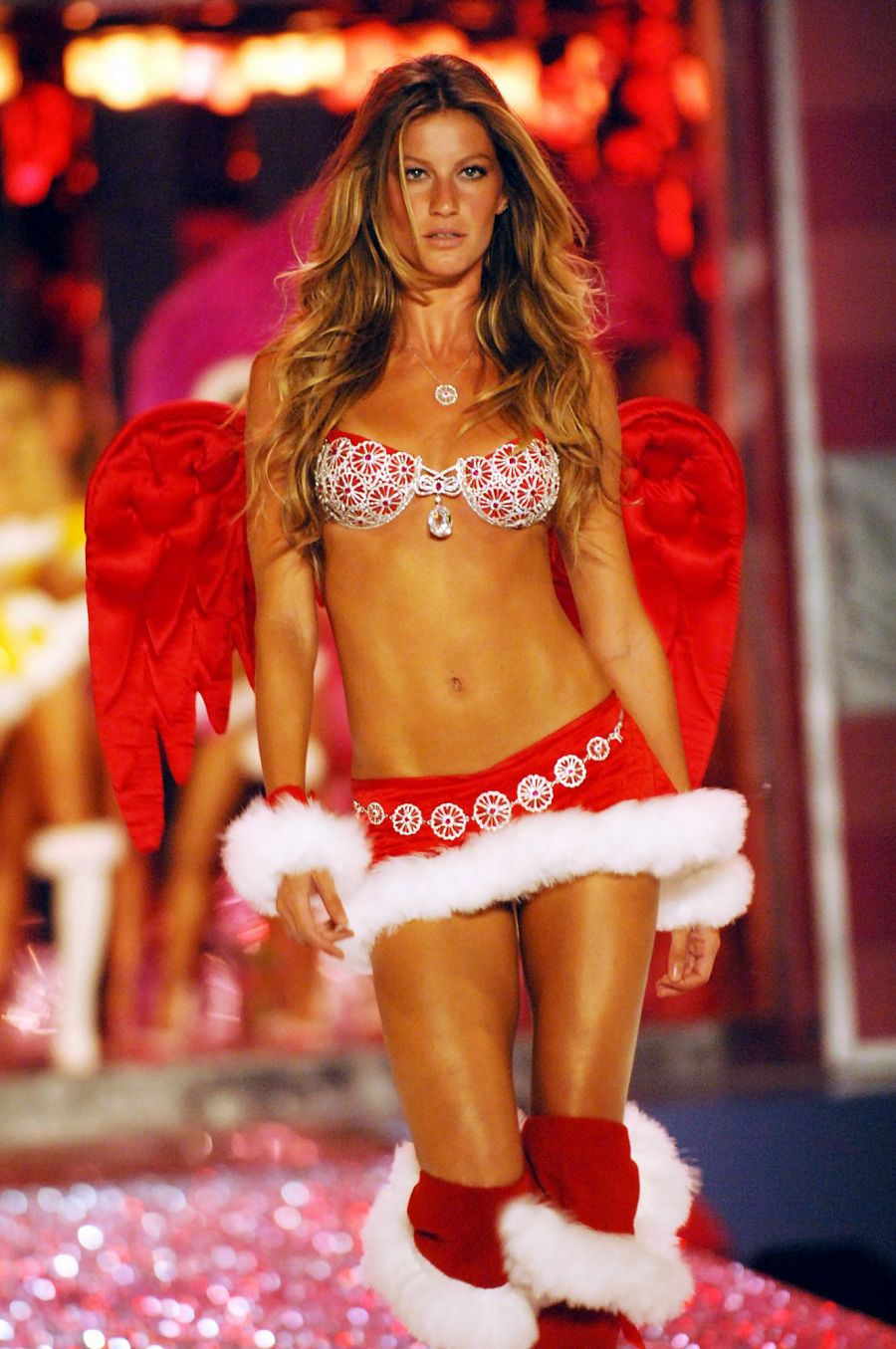

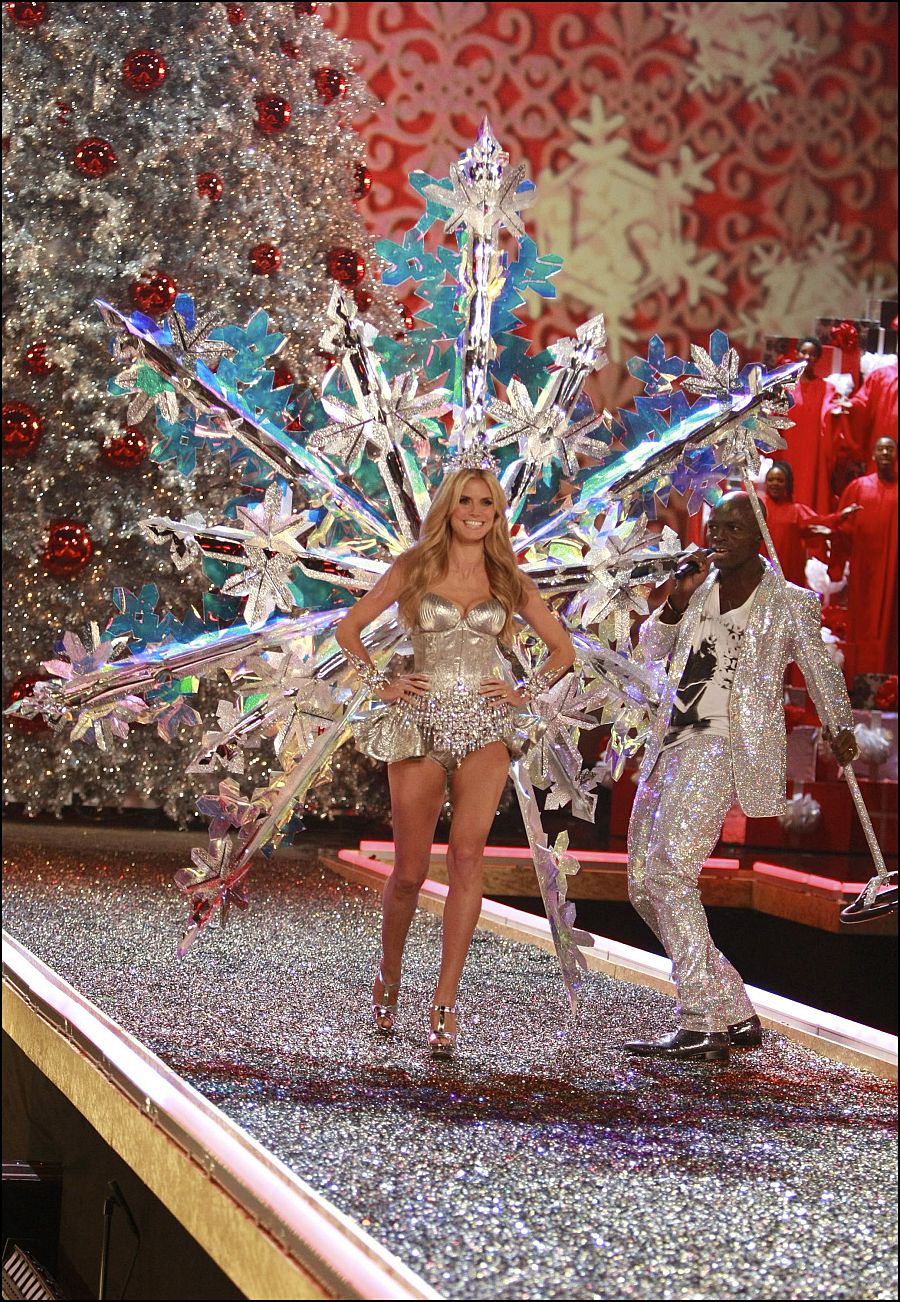

The American lingerie chain has spent the last two years overhauling its hyper-sexualized image in a bid to regain cultural relevance and win back young consumers who preferred more on-trend upstarts like Savage X Fenty and Parade.

There were some successes, including a campaign to launch the “new” Victoria’s Secret featuring soccer player Megan Rapinoe, transgender model Valentina Sampaio and other spokesmodels, but favorable reviews from online critics never translated into sales: the brand is projecting revenue of $6.2 billion this fiscal year, down about 5% from the previous year and well below the $7.5 billion from 2020.

More recent campaigns have featured models like Hailey Bieber and Emily Ratajkowski, who would have fit right in with Heidi Klum and Adriana Lima at the 2007 show, as well as new-look ambassadors, including plus-size models Paloma Elsesser and Ali Tate-Cutler.

Victoria’s Secret: The Tour ‘23, an attempt to revive the runway show format that launched last month fell somewhere in between the personification of male lust of the brand’s aughts-era heyday and the inclusive utopia promoted by its many disruptors.

But in a presentation to investors in New York last week, it was clear which version of the brand Victoria’s Secret executives see as its future.

“Sexiness can be inclusive,” said Greg Unis, brand president of Victoria’s Secret and Pink, the company’s sub-brand targeting younger consumers. “Sexiness can celebrate the diverse experiences of our customers and that’s what we’re focused on.”

The prime objective? Improve profitability and cross back over $7 billion in annual sales. That means investing in new categories, including activewear and swim, updating its nearly 1,400 Victoria’s Secret and Pink stores and opening 400 new locations outside North America. Costs will also be cut and, judging from the messaging at the investors presentation, fewer risks taken when it comes to the brand’s image.

“Despite everyone’s best endeavours, it’s not been enough to carry the day,” said chief executive Martin Waters.

New clothes, new stores

Waters talked of a challenged retail sector and a consumer who’s choosing off-price alternatives as her wallet continues to be squeezed by inflation.

To win that customer back, Victoria’s Secret is offering its shoppers products beyond bras, underwear and pyjamas.

This means returning to swimwear and activewear, two categories that the retailer exited in recent years. At one point, activewear was a $500 million business for the company, Unis said, with 16 percent share of the sports bra market. Today, that segment is far smaller and only commands a 4 percent share.

Additionally, the brand intends to increase other apparel offerings such as loungewear, sweaters, slip dresses and corset tops — pieces that are adjacent to its forte in sleepwear and lingerie, Unis said. Within Pink, Victoria’s Secret will focus on improving the assortment of fleeces, sweatpants, tracksuits and other casual pieces.

Perhaps the most drastic departure from the Victoria’s Secret of the past is its new bricks-and-mortar look. The brand began revamping its retail locations in 2021, eliminating the dark, austere feel of the stores that may have been trendy in the aughts but no longer resonates with today’s shoppers.

The retailer’s “store of the future” will feature bright but warm lighting, soft decor, a wider entryway and an overall welcoming atmosphere. Even the fixtures are smaller and rounded, painted in a soft pink tone to evoke intimacy with the consumer, said Albert Gilkey, senior vice president of store design and construction at the company.

The Elephant in the Room

Victoria’s Secret began its modern makeover in part due to competition from digital newcomers — brands such as ThirdLove and Parade, that wooed consumers with inclusive marketing and progressive language.

The threat of their disruption, however, has largely diminished in recent months as the direct-to-consumer bust continues to play out and digital marketing costs have become unsustainable for brands with only an e-commerce presence. Parade was recently sold to Ariela & Associates International, a bra licensing company that manufactures products for Fruit of the Loom.

But Rihanna’s Savage X Fenty brand remains a force to be reckoned with, and Aerie poses steep competition for Pink with younger consumers. A potentially even more formidable contender is gaining ground too: Skims, the shapewear brand co-founded by Kim Kardashian, raised funding in July at a $4 billion valuation. The brand projects it will reach $750 million in sales this year, well below Victoria’s Secret’s $6 billion-plus but far ahead of many other would-be challengers. An IPO would give Skims the resources to rapidly open stores and take on Victoria’s Secret directly.

Unis was unfazed. How Victoria’s Secret ventures into apparel will be conservative in manner, he said, and will follow a test-and-learn approach.

For all its problems in recent years, Victoria’s Secret is still the largest underwear retailer in North America, with about 20 percent of the market share, according to its own analysis.

“We’ve been insufficiently differentiated in this difficult market,” Waters said. “(But) our ambition of being the world’s leading fashion retailer of intimates apparel is unchanged.”